AI can’t replace humans, but the technology is making inroads in more and more business sectors.

Here’s a closer look what companies and researchers across Florida are doing with AI technology and why the experts say it will never completely replace humans.

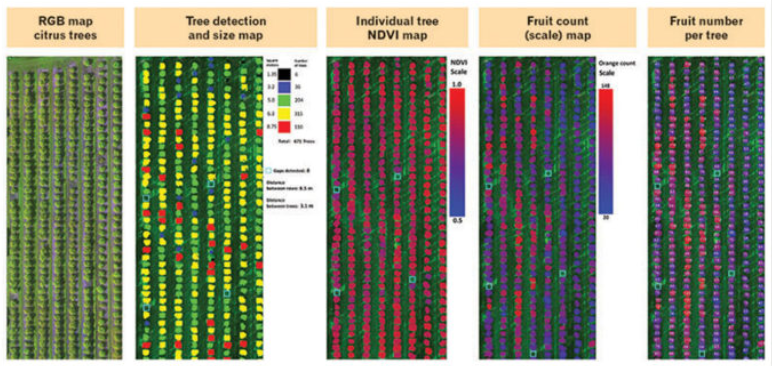

Gaps in Groves

UF technology is helping orange growers count their trees and optimize tree growth.

Orange trees were easier to count before citrus greening struck. Fields were relatively uniform then, and farmers who had planted 160 trees per acre on 10 acres knew with reasonable certainty that they had about 1,600 trees. But when greening swept through Florida about a decade ago, groves became riddled with gaps where diseased and dead trees once stood. To get an accurate count, growers had to hire workers to drive through their groves, counting each tree, one by one, with a clicker.

“It was very time consuming and very expensive,” says Yiannis Ampatzidis, a University of Florida scientist stationed in Immokalee. To address the problem, Ampatzidis and his research team developed a system called Agroview that uses special images taken from drones and the ground to count the trees and assess their conditions. The method isn’t perfect, but it’s close. It tallied 175,977 citrus trees at one Hendry County farm with close to 98% accuracy. It’s also quick, taking about 10% as long as a manual count.

Florida growers seized on the technology in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture began requiring them to submit accurate tree inventories to maintain insurance coverage. Others have used Agroview to pinpoint gaps in groves so they can replant where dead trees once stood. Growers can also use the technology to detect disease and optimize the health of plants.

Agroview combines multispectral imaging and leaf analysis. The drones carry special cameras that capture image data of the trees across a broad portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, including wavelengths invisible to the eye. Data from those images are then fed into Agroview’s AI software, where they’re cross-referenced with data from leaves that have been analyzed in labs to identify plants with nutrient deficiencies, diseases or other types of stress. Armed with that information, growers can fine-tune their application of fertilizer, pesticide and other inputs. If the system indicates low levels of nitrogen or phosphorus, for instance, the grower can increase his application of those nutrients in the affected areas. If nutrient levels are high, the grower can ease up. If disease is detected, the grower can apply a treatment early, before it spreads through the entire crop.

Farmers can purchase Agroview through a UF spinoff company called Agriculture Intelligence. The company will also collaborate with drone operators if growers don’t have their own drone to collect the data. “Right now, we’re working mainly with citrus, but tomato and other crops, other profiles, will come soon,” Ampatzidis says.

UF researchers are also collaborating with a farm equipment company in [Lake Wales] called Chemical Containers to develop a “smart sprayer” that uses AI and “sensor fusion” for precise application of insecticides and weed killer. “If you have a traditional sprayer, it will spray everywhere with the same amount, but that doesn’t make sense,” Ampatzidis says. “If you have a big tree, you need more chemicals to be sprayed, but if it’s small, half the size, in theory you need half. If it’s a gap, you don’t spray at all.”

Original Article authored by Amy Keller in Florida Trends magazine